Querying block device sizes in Python on Linux and Mac OS X

I drafted this blog post in 2016 (at least), but held off publishing it until I could have it fact checked. Well, 6 years have passed… I am 99% sure the information in this blog post is correct. But if you find an error with my explanation of the userspace-kernel-device dataflow then please send me an email so I can understand it better and update this post. Thank you!

Updated: 2025-06-06 - Fixed missing ioctl flow image. Sorry about that!

⦾ The Problem

I've been experimenting with creating functionality within bitmath for reading the size of storage devices. This would provide a function similar to Python's os.path.getsize, but for storage device capacity instead of file sizes.

Unfortunately, it turns out that there is no out of the box (and cross-platform) solution in Python for reading the capacity of system storage devices. This meant some research was going to be required. Luckily, possible solutions for how to do this are abundant across the internet. Well, for Linux anyway. Figuring out how to make this work on Mac OS X was more challenging.

And that's where the story gets interesting.

In the rest of this blog post we'll learn the basics of how programs can interact with storage devices via the ioctl() system call. Then we'll discuss the things we have to do and information we'll need to have in order to implement an ioctl() request in Python. Next we'll see how to gather all the necessary information (request codes and expected result sizes). Finally we'll put all of this together into a runnable Python program.

If you're not familiar with that acronym, "ioctl" stands for "input/output control".

⦾ Back to Basics

Before we start learning how to query a storage device's capacity in Python we're going to review (from a very high-level) the core concept of this exercise: ioctl() requests and how the operating system handles them.

ioctl requests are just one of many types of system calls. ioctl requests enable processes to interact with (read from, write to) storage devices. Generally speaking, to make an ioctl call we need a reference to the device to which the call will sent to, and a request code to send to the device. Additionally, because of how the ioctl requests we make in this blog post are implemented, we'll also need to create a buffer. This buffer is basically a specially sized empty variable for the kernel to store the request result in. Specifically, it is a region of memory reserved for the ioctl() call result.

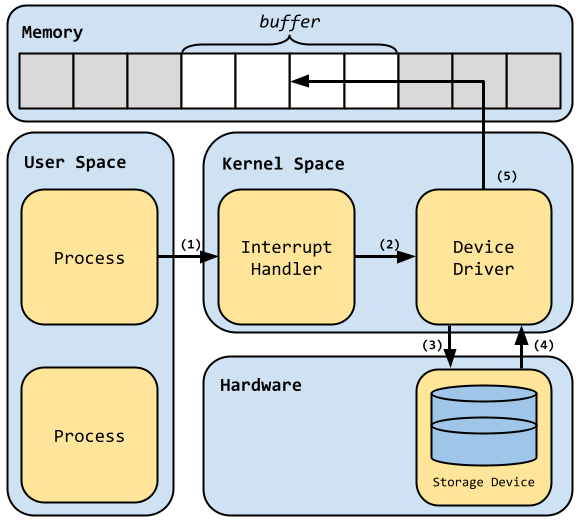

The following image shows the general flow of control/data when a process has issued an ioctl() request. Following the image we'll review what happens at each numbered transition.

Flow of control/data when handling ioctl requests:

-

In this first transition, a process issues a call to the

ioctl()library call, this in turn causes a software interrupt, the result is execution control immediately switches over to the kernel interrupt handler -

The interrupt handler looks at the provided ioctl request code and uses it to locate and call the correct function in the device driver subsystem to handle the request

-

In the third transition the driver then executes the device specific instructions to fulfill the request

-

Back in kernel space, the storage device response has been received

-

Finally, before the original process can read the response, the device driver must copy the response into the pre-allocated buffer region for the application to use as necessary

To briefly review: a process makes an ioctl() function call specifying a certain device, request code, and a region of memory identified by the pointer called buffer. When the ioctl call is executed by the CPU an interrupt is raised which instantly switches the flow of execution into privileged kernel space. The kernel finds and runs the function which handles the given ioctl request. Once the storage device responds with a result, the result is copied into the memory region called buffer. After this is complete, the flow of control returns back to the original process running in user space.

⦾ Coding Review

The Python standard library includes two important modules we'll be using:

-

fcntl - For access to the

fnctl.ioctlfunction. This is how we actually execute the ioctl request. -

struct - For it's

struct.unpackfunction. This is how we translate the "packed" binary response from the device into a familiar datatype.

Here's a general review of how these functions are used in concert:

-

The application creates a properly sized buffer variable to store the future results in

-

The ioctl call is made, specifying the device, request code, and the buffer variable

-

If the request succeeds, the buffer string variable is now a

packed c struct. We'll learn more about this strange entity later -

The result is unpacked into a normal Python datatype

Use of these module functions appears rather simple. What makes this an interesting problem isn't the code necessarily, but rather the investigation work required to supply these functions with correct inputs. As reviewed already, to make an ioctl() call we need three pieces of information:

-

A reference to the target device

-

The exact request code representing the request we're making of the device

-

A pre-sized buffer variable for the kernel to store the result in

Each operating system maintains a unique set of request codes for each class of device. Additionally, each operating system may have a unique symbolic name for each request code.

In addition to the unique request codes, each request which returns information needs a properly sized variable to store that information in, and the required size of that variable is unique to different requests. That is to say, some requests may need 8 bytes of memory to store results in, whereas other may only require 4. Some request results may be numerical values, whereas others could be strings or floating point values.

Sounds fun, right? Let's dig into some implementation specifics now.

Knowing the expected datatype (fmt) of the request response, we use the struct.unpack function to unpack the buffer string into the specified format. Formats are specified by means of special formatting characters which are basically short-hand ways to tell struct.unpack what you want to turn the variable into.

For example, for a call which would return (in C code) an unsigned long, we would use the L formatting character with struct.unpack. According to the Table of Formatting Characters, the L format will turn an unsigned long C type into a Python integer type. That's great to know because the calls we'll be making will return integers.

There's still a few more pieces of information we need to uncover before we can get started. We need the hexadecimal request codes used on Linux and Mac OS X when making the ioctl calls. This is when the problem got really interesting to me.

⦾ Request Codes

The approach we will take to finding the necessary request codes is applicable to all operating systems. We'll write some small C programs which include some required headers and then print out the hex value of the symbols we're interested in.

"Wait! Why are these hex values so important?", you may be asking. The answer is because when we write our Python script we must use the request codes actual value. Symbol names (i.e., BLKGETSIZE64) are not accepted.

⦾ Linux

Querying the block device size in Python on a Linux host was as simple as copying and pasting the example code provided in this stackoverflow answer. You can see in here on line number 6 that the original poster was

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-readsize-py

⦾ How This Works

Having a working example is nice and all, but understanding how it works is more important if we're going to make it run on OS X as well. Let's begin by returning to basics, and that means talking about system calls, specifically the ioctl (input/output control) system call.

Now why is this a challenge to port from Linux to Mac? Why doesn't the same code run on both operating systems? Shouldn't it just work?

Now, let's return to our original example. See that line which reads req = 0x80081272? That is the request code we're going to send to the block device. The original author was kind enough to include the symbol name for this request code as well, BLKGETSIZE64. This is a good thing to know because we're going to need that same type of information to make this all work on Mac OS X.

⦾ Symbol Name To Code Value (Linux)

I hope you have a C compiler installed, because we're about to get weird in here. How do we go from a symbol name to the symbol value? On Linux, the request code we're using is defined in the kernel header file /usr/include/linux/fs.h. Below is a small C program which loads this header and prints out the hex value of this symbol for us. We'll do a similar thing on OS X in a later example.

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-linux-request-code-c

Compile and run this code like this:

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-linux-compile-run-request-code-sh

Note how the printed value matches the value in our original Python code sample. That is how we go from request code symbolic names to request code numerical values.

⦾ Request Codes on Mac OS X

Now we'll use what we learned above to find the same type of information for OS X. Figuring this out required additional research. As previously noted, the symbol name is not going to be the same on OS X. In fact, research showed that we will need to know two request codes on OS X. This is because OS X does not have a single request code equivalent to the Linux BLKGETSIZE64 code.

Below is the C code from the referenced research. The code shows us how to calculate the disk size in bytes on OS X, it also tells us the names of which request codes we'll need to find the values of (but still no code values).

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-osx-calclulate-disk-size-c

Things to note from this example:

-

Instead of including

linux/fs.hwe must includesys/disk.h -

BLKGETSIZE64is not used here (Linux exclusive!), instead two ioctl request results are multiplied together:-

DKIOCGETBLOCKSIZEto find the size of each block -

DKIOCGETBLOCKCOUNTto find the number of blocks on the disk

-

⦾ Symbol Name To Code Value (Mac OS X)

To obtain the request code values on OS X we will roughly repeat the same process we used on Linux. We'll write a small C program, include the header, and print out the hex values.

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-osx-request-code-c

Compile and run that example:

https://gist.github.com/tbielawa/d49b6e7a057377f6a0ee#file-osx-compile-run-request-code-sh

From this we now know the value of the required request codes for OS X and Linux:

⦾ Request Codes Review

| OS | Symbol | Value |

| Linux | BLKGETSIZE64 |

0x80081272 |

| OS X | DKIOCGETBLOCKSIZE |

0x40046418 |

| OS X | DKIOCGETBLOCKCOUNT |

0x40086419 |

⦾ Handling struct.unpack()

Nearly done now! Let's return once again to the original Python code earlier in this blog post. On line 12 we see this statement: bytes = struct.unpack(fmt, buf)[0] and fmt was set to L earlier in the example. What does this mean, and why do we do it?

When we make the ioctl request with Pythons fcntl.ioctl function, the value we get back in the buffer variable is a binary structure (think of C structs) which has been "packed" into a string. That is to say, instead of fcntl.ioctl returning an integer representing our disk size in bytes, we receive a string representing the binary equivalent of this value. To turn this into something useful we must unpack the string into a data-structure native to Python. Unpacking binary data in Python is done the same way for each packed value, using struct.unpack. The difference between unpacking each type is in deciding what to unpack the data into, and that requires knowing the size of the data we're going to unpack.

Every ioctl request will return a value of a known size. These variable sizes are documented in the kernel headers source code. In the case of BLKGETSIZE64 specifically, this is defined in /usr/include/linux/fs.h as such:

#define BLKGETSIZE64 _IOR(0x12,114,size_t) /* return device size in bytes (**u64** *arg) */

That part at the end in bold, u64, is what we're interested in. This indicates that the ioctl request returns an unsigned 64-bit integer type variable. This is also known as an unsigned long type variable. We now know the size and type of the data we're going to unpack. Next we consult the struct modules Table of Formatting Characters to identify which formatting character we will use when we call struct.unpack on our packed data. According to the table, the L formatting character is equivalent to the unsigned long c type (which becomes a Python integer once unpacked).